Background and purpose

Background

Coastal and island Biosphere Reserves are highly vulnerable to coastal hazards, which will become more frequent and intense due to climate change.

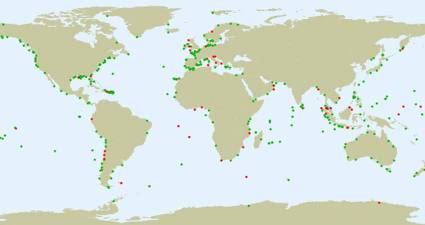

Biosphere Reserves are UNESCO-designated sites which promote solutions reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use. A 2015 UNESCO survey found that 84 percent of Biosphere Reserves—UNESCO-designated areas that promote management approaches and solutions which reconcile conservation of biodiversity with sustainable use—considered natural hazards to be an important issue. The 2015 survey and a follow-up survey in 2017 found that 89% and 94%, respectively, of Biosphere Reserves are exposed to natural hazards. In fact, natural hazards have already caused significant damage to several UNESCO-designated sites. As such, there is an urgent need to increase disaster risk reduction (DRR) within Biosphere Reserves. Few DRR plans and procedures sufficiently accounting for the threat of inundation and damage from tsunamis and other coastal hazards have been developed for Biosphere Reserves globally.

Although most coasts worldwide are threatened by coastal hazards, Costa Rica is particularly vulnerable due to exposure across both its Pacific and Caribbean coastlines. The coastal hazards which are specifically threatening to Costa Rica include tsunamis, storm surges, and urban flooding from heavy rainfall. Since 2014, the Sistema Nacional de Monitoreo de Tsunamis de Costa Rica (SINAMOT) Programme—Costa Rica’s National Tsunami Warning Centre (NTWC)—has recorded over 350 potentially tsunamigenic events, four of which caused tsunamis registered in Costa Rica. On 15 January 2022, the Hunga-Tonga volcanic eruption caused a tsunami which was registered across the Pacific basin, including in Costa Rica. In addition, in June 2021, the urban centre of Quepos, a city within the Savegre Biosphere Reserve, was flooded due to heavy rainfall and inundation from the Quebrada Padre which runs through the city centre.

The Savegre Biosphere Reserve is the only coastal and marine Biosphere Reserve in Costa Rica. Located approximately 190km southwest of San Jose along the Central Pacific coast, it boasts a high level of biodiversity and endemism. It is also a socially and economically significant area, with a population of 50,000 inhabitants as well as a significant and growing number of tourists and seasonal visitors. The Savegre Biosphere Reserve is particularly vulnerable to coastal hazards because it attracts thousands of visitors every year and is home to diverse populations, including vulnerable and at-risk populations living in more remote areas. Since tourism is a primary source of income for Costa Rica and for this region specifically, developing preparedness and response mechanisms for coastal hazard risk in this area is critical to save lives and livelihoods. Economic strain and the need for economic recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic has placed further importance on safeguarding socio-economic opportunities in the Savegre Biosphere Reserve. Moreover, risk of and impacts from coastal hazards are expected to become more severe due to climate change.

Purpose

While most coastal hazards cannot be prevented, risks and vulnerability can be reduced through programmes that develop resilient communities and build preparedness capacities.

In response to the identified need to develop preparedness to coastal hazards in the Savegre Biosphere Reserve, the Joint Initiative of the Tsunami Unit (TSU) of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) and UNESCO Man and Biosphere Programme (MAB) established their Joint Initiative “Integrated approach to coastal hazards in the Savegre Biosphere Reserve, Costa Rica: saving lives, protecting biodiversity”. The project benefits from and builds on the complementary expertise and experience of both groups. It was launched in July 2021 and is due to be completed in autumn 2022. It focuses on three areas of the Savegre Biosphere Reserve: the urban centre of Quepos, Manuel Antonio, and the Parque Nacional Manuel Antonio. These communities were selected as they are particularly vulnerable to coastal hazards due to population density, the presence of coastal stretches and beaches, and important economic, including tourism, fishing, and agriculture.